PDF available HERE.

Serpiginous Choroiditis versus Presumed Tuberculous Serpiginous‑Like Choroiditis: A Case Report and Focused Review

Ljubo Znaor 1,2,*, Ana Vučinović 1,2, Žana Ljubić 1

1 Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Split, Split, Croatia

2 Department of Ophthalmology, University of Split School of Medicine, Split, Croatia

* Correspondence: ljubo.znaor@kbsplit.hr

Abstract

Background: Serpiginous choroiditis (SC) is a rare, recurrent inflammatory chorioretinopathy of the outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choriocapillaris. Tuberculosis-associated serpiginous-like choroiditis (TB-SLC) can closely mimic classic SC but requires a different diagnostic work-up and therapeutic approach.

Methods: We report a case of bilateral posterior uveitis with serpiginoid lesions involving the peripapillary and macula. Multimodal imaging available at presentation and systemic evaluation revealed a strongly positive tuberculin skin test with no evidence of systemic tuberculosis.

Results: A 45‑year‑old man presented with central and paracentral scotomas. Examination showed grayish‑yellow subretinal lesions in both eyes with a peripapillary geographic lesion in the right eye. Tuberculosis skin test was strongly positive, chest x‑ray was normal. Based on clinical phenotype and immunologic findings, the case was classified as presumed ocular tuberculosis presenting as serpiginous-like choroiditis. The patient was treated with antitubercular therapy combined with corticosteroids and later azathioprine resulting in the stabilization of vision in the right eye.

Conclusions: Phenotype-directed evaluation, including tuberculosis testing, is essential before escalation of immunosuppression in patients with serpiginoid choroiditis. In cases consistent with presumed TB-SLC, timely antitubercular therapy combined with controlled anti-inflammatory treatment may limit progression and preserve vision.

Keywords: serpiginous choroiditis; serpiginous‑like choroiditis; presumed ocular tuberculosis; antitubercular therapy; posterior uveitis

1. Introduction

Serpiginous choroiditis (SC) is an uncommon, often bilateral posterior uveitis characterized by recurrent, geographic lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), outer retina, and choriocapillaris that typically begin at the juxtapapillary region and extend centrifugally. A clinically similar entity, serpiginous-like choroiditis (SLC), is most commonly associated with tuberculosis (TB) and differs from classic SC in etiology, diagnostic framework, and management. TB-SLC closely mimics autoimmune SC in appearance, but typically manifests with multifocal, non-contiguous placoid lesions, vitreous inflammation, and peripheral retinal involvement. Accurate differentiation is critical because management diverges: immunosuppression for classic SC versus full antitubercular therapy (ATT) with carefully titrated anti‑inflammatory treatment for TB-SLC (1–3,6,7,9). Multimodal imaging (fundus autofluorescence, fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography, OCT/OCT‑A) together with TB testing (Mantoux/IGRA, chest imaging, and, when feasible, intraocular fluid polymerase chain reaction) guide diagnosis and follow‑up (5–9).

2. Case presentation

A 45‑year‑old man presented with a 3‑day history of central and paracentral scotomas in both eyes, more pronounced in the left eye. He reported no prior systemic illness, no known TB exposure, and no constitutional symptoms. The patient could not recall his BCG vaccination history. A deltoid scar suggestive of prior BCG vaccination was noted on examination. Smoking history was significant (approximately 40 cigarettes/day). Best‑corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 1.0 in the right eye and 0.02 in the left eye. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable bilaterally, with no signs of intraocular inflammation. Intraocular pressures were 15 mmHg in both eyes. Fundus examination of the right eye revealed contiguous peripapillary grayish-white geographic lesion extending centrifugally, accompanied by three discrete grey-yellow placoid subretinal lesions in the temporal macula, including one parafoveal lesion. No vitreous inflammation was present. In the left eye, a solitary grey-yellow placoid lesion was centered at the fovea, without vitritis. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated early hypofluorescence of the lesions with late staining of lesion borders, without evidence of retinal vasculitis. Laboratory evaluation showed normal complete blood count and inflammatory markers. Serology was positive for HBsAb, HBcAb, indicating past hepatitis B exposure, and for Toxoplasma gondii IgG; consistent with prior exposure. Serology was negative for HBsAg, HBeAg, HCV, HIV, and syphilis. Tuberculin skin testing was strongly positive (25×25 mm). Chest radiography and urinalysis were unremarkable. Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) testing was not performed, in accordance with local diagnostic practice at the time. No chest CT, sputum testing, or intraocular fluid analysis was pursued due to the absence of systemic symptoms and the invasive nature of these procedures. Based on the clinical phenotype and immunologic findings, the case was classified as presumed ocular tuberculosis presenting as serpiginous-like choroiditis.

Given the serpiginoid phenotype and strongly positive tuberculin skin test, antitubercular therapy (ATT) was initiated with rifampicin 600 mg/day, isoniazid 400 mg/day with pyridoxine supplementation, and ethambutol 1600 mg/day. Systemic corticosteroid therapy was started concurrently with oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day, and gradually tapered. Adjunct retrobulbar dexamethasone was also applied. During follow-up, BCVA in the right eye transiently declined to 0.8, prompting the addition of Azathioprine at 1.5 mg/kg/day under ATT cover. At 6‑months, BCVA was 1.0 in the right and remained 0.02 in the left eye, the letter reflecting irreversible foveal involvement at presentation.

3. Imaging findings

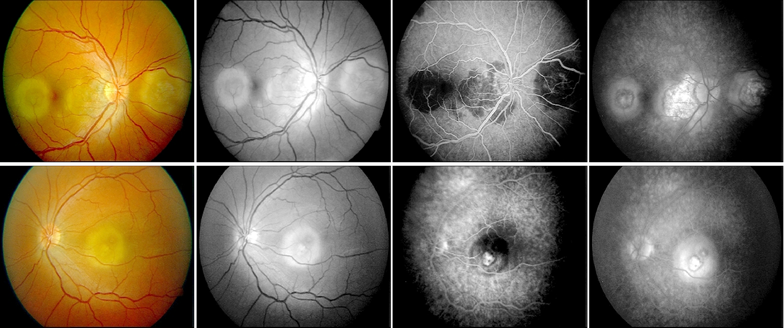

Color fundus photographs of the right eye showed a contiguous peripapillary geographic lesion with multifocal gray-yellow placoid lesions extending temporally, while the left eye demonstrated a solitary fovea-centered placoid lesion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fundus photographs and fluorescein angiography at presentation showing peripapillary and macular lesions.

Upper raw figures represent the right eye, lower raw images represent left eye.

Fluorescein angiography revealed early hypofluorescence of active lesions with late staining at the margins, consistent with serpiginoid inflammatory activity. At the time of presentation, optical coherence tomography (OCT), fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) were not available at our institution; therefore, imaging assessment was limited to color fundus photography and fluorescein angiography. ICGA can delineate choroidal non‑perfusion and occult active margins (5,7–9). Follow-up fundus photography at six months demonstrated stable chorioretinal scarring without evidence of lesion progression or recurrence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Follow-up color fundus photographs six months later demonstrating stable scarring without recurrence.

At 10-year follow-up, the fundus findings remain stable with no evidence of recurrence or new lesions, confirming durable disease quiescence under previous treatment.

4. Discussion

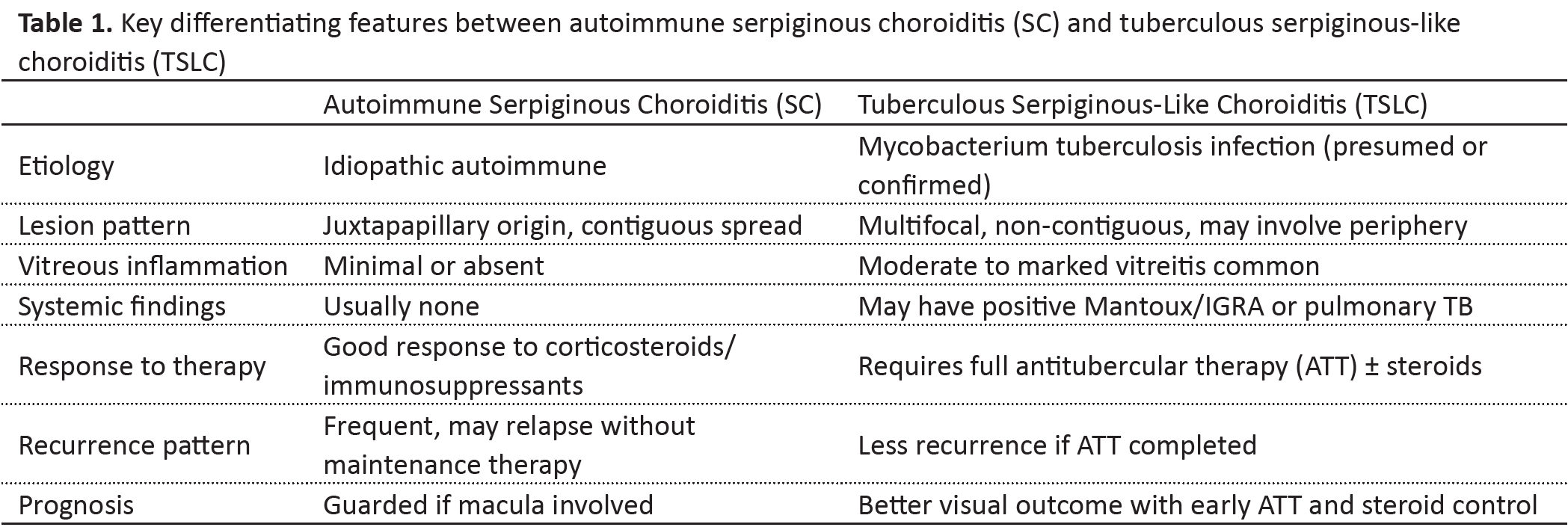

The principal diagnostic challenge in this case was distinguishing classic autoimmune SC from TB‑associated serpiginous‑like choroiditis (TB-SLC). Classic SC typically presents with contiguous peripapillary spread and minimal vitreous inflammation, whereas TB-SLC more often demonstrates multifocal or placoid lesions, may involve the macula early, and is associated with positive tuberculosis testing (1–3,5–7,9,12). The key clinical, imaging, and therapeutic features that help differentiate classic autoimmune serpiginous choroiditis from tuberculous serpiginous-like choroiditis are summarized in Table 1. Similar to our case, several reports describe tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis presenting with macular involvement and positive TB immunologic testing, even in the absence of systemic disease (13). The differential diagnosis of serpiginoid choroiditis includes ampiginous choroiditis, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, sarcoidosis, syphilis, and toxoplasmosis. In this case, syphilis and sarcoidosis were excluded by serology and clinical findings. Although Toxoplasma IgG was positive, the absence of focal necrotizing retinitis, vitritis, and typical lesion morphology made toxoplasmosis unlikely. Multimodal imaging aids differentiation: FAF can reveal advancing borders and patterns favoring one phenotype; ICGA may show wider choriocapillaris non‑perfusion; OCT documents outer retinal/RPE disruption and, in acute inflammatory choroidopathies, bacillary layer detachment (BLD) indicating exudation (5,7,10,11).

Management strategies differ substantially between SC and TB-SLC. In presumed TB‑SLC, consensus supports initiating full ATT when supportive evidence exists, combined with systemic corticosteroids to limit inflammatory damage and paradoxical reactions; selected cases may require adjunct immunosuppression under ATT cover (2,3,6,9,15). Intravitreal corticosteroid implants can be considered for macular edema or localized exudation with appropriate antimicrobial coverage (4,6,10). Biologic agents (anti‑TNF) may help refractory autoimmune SC, but they carry a significant risk of TB reactivation even after negative screening and therefore require extreme caution (10,14). Our patient’s strongly positive tuberculin skin test and phenotype led to ATT with controlled anti‑inflammatory therapy, stabilizing vision in the right eye. Persistent poor vision in the left eye likely reflects foveal structural damage at presentation, underscoring the prognostic impact of macular involvement (4,11,16).

The limitations of this report include the absence of microbiological confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, lack of IGRA testing, HBV DNA testing, and unavailability of OCT, FAF, and ICGA imaging at the time of presentation. These factors limit etiologic certainty but reflect real-world constraints in retrospective case analysis.

5. Conclusions

In patients presenting with serpiginoid chorioretinal lesions, careful phenotypic assessment and tuberculosis evaluation are essential before escalation of immunosuppression. When findings support presumed ocular tuberculosis presenting as serpiginous-like choroiditis, timely antitubercular therapy combined with appropriately titrated anti-inflammatory treatment may preserve vision and prevent progression.

Acknowledgments: We thank the clinical staff of the Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital Centre Split.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, L.Z.; data acquisition and clinical management, L.Z. and A.V.; literature review and manuscript drafting, Ž.L.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. and Ž.L. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding

Ethics statement: Not applicable (single anonymized case report).

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case and images.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

6. References

- Rodríguez-Vidal C, Galletero Pandelo L, Artaraz J, Fonollosa A. Bacillary layer detachment in a patient with serpiginoid choroiditis. Indian J Oph. 2022;70(7):2687-9. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2174_21

- Bansal R, Gupta V. Tubercular serpiginous choroiditis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2022;12(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s12348-022-00312-3

- Vianna RNG, Vanzan V, da Fonsêca MLG, Cravo LM. Unilateral macular serpiginous-like choroiditis as the initial manifestation of presumed ocular tuberculosis. Int J Retin Vitr. 2021;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40942-020-00272-7

- Perlman EM, Greenberg PB, Browning DJ, Friday RP, Miller JW. Solving the hydroxychloroquine dosing dilemma with a smartphone app. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(2):218–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6076

- Zafar F, Bibi H, Khan S. Evolution of placoid inflammatory lesions of tuberculous serpiginous-like choroiditis on OCT and blue autofluorescence. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2025;37(1):178–82. doi: 10.55519/JAMC-01-11619

- Saurabh K, Panigrahi PK, Kumar A, Roy R, Biswas J. Profile of serpiginous choroiditis in a tertiary eye care centre in eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(11):649–52. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.119409

- Znaor L, Medic A, Karaman K, Perković D. Serpiginous-like choroiditis as sign of intraocular tuberculosis. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(7):88–90. doi: 10.12659/msm.881839

- Lambrecht P, Claeys M, De Schryver I. A Case of Ampiginous Choroiditis. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2015;6(3):453–7. doi: 10.1159/000442742

- Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of serpiginous choroiditis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52(4):229–36. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318265d474

- Balarabe AH. Clinical profile and outcome of serpiginous choroiditis in a Uveitis Clinic in India. Niger J Ophthalmol. 2014;22(1):24–6. doi: 10.4103/0189-9171.142751

- Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification criteria for serpiginous choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;Aug228: 126-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.038

- Moorthy RS, Zierhut M. Serpiginous choroiditis. In: Zierhut M, Pavesio C, Ohno S, et al., editors. Intraocular inflammation. Berlin: Springer; 2016. p. 1021–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75387-2_94

- Guedes ME, Galveia JN, Almeida AC, Costa JM. Tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis. Case Reports 2011;bcr0820114654. doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2011.4654

- Papasavvas I, Jeannin B, Herbort CP Jr. Tuberculosis-related serpiginous choroiditis: aggressive therapy with dual concomitant combination of multiple anti-tubercular and multiple immunosuppressive agents is needed to halt the progression of the disease. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2022;12(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12348-022-00282-6

- Khalsa A, Kelgaonkar A, Basu S. Anti-TB monotherapy for choroidal tuberculoma: an observational study. Eye (London, England). 2022;36(3):612–618. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01505-1

- Lim WK, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Serpiginous choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(3):231–44. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.02.010